Ethics, morality, codes, mantras and a sense of responsibility often fail to attach themselves to successful business strategies, and the results leave behind negative impacts that fall into the laps of others. While the oil and gas industry has made strides in improving production techniques and weighing potential harmful environmental impacts, a growing problem continues to surface. As companies and assets change hands and wells play out, landowners are left holding the bag with orphaned wells. Having identified the problem and driven by a heightened sense of right and wrong, Curtis Shuck decided to take matters into his own hands and crusade to clean up a mess that increasingly gets passed down the line.

Driven by production results, the oil and gas industry exerts great effort into the potential of a well. The costs associated with planning, engineering, drilling and completing a well command a high value, so great attention is directed at bringing the well online. Profits are earned once the well starts producing. Guided by safety programs, these companies brave harsh weather conditions and overcome logistical issues to accomplish the task. However, when the well completes its life cycle, it draws less attention as it focuses on the following well with potential earnings. As a result, oil and gas companies move on, and sometimes nonproducing wells are left orphaned or abandoned. Although they might not produce, they can emit harmful gases and display a dangerous reach in additional areas.

“Abandoned wells not only pose the potential to release harmful gases to the atmosphere, but they can also cause other problems,” says Shuck. “They can leak and pollute the surface area and even interface with the drinking water, imposing significant harm.”

Shuck visited the Kevin-Sunburst oilfield in northern Montana in 2019 and was astounded to witness the negative impact of orphaned and abandoned oil and gas wells levied against communities and the environment. What he saw vastly differed from how he had conducted himself within the industry.

“I was absolutely horrified to find things in the condition they were in,” says Shuck. “I was embarrassed as an industry professional.”

Drawing upon an oil and gas career that began in 1982, Shuck knew he could make a difference and turn things around. In response, he founded the Well Done Foundation (WDF) and vowed to leave the oil patch in better condition than the way he found it.

“I had no idea what I was getting into,” says Shuck, “but I knew I had to do something.”

Early Career

Shuck drew upon his extensive oil and gas career to identify a premier issue and then devise a strategy of correction. For over 30 years, he has directed his public service and private sector experience with oil and gas, including transportation project development, delivery of capital projects, and business development dealings within the Pacific Northwest and the Mid-Continental United States. However, his career began when he took a roustabout position on Alaska’s North Slope in the summer of 1982.

With 20 years of public service experience, Shuck joined the Red River Oilfield Services, Inc., team in Williston, North Dakota, the heart of the Bakken formation. As vice president of business development in 2015, his primary responsibilities included growing and supporting Red River’s transportation and logistics programs. He later climbed the corporate ladder to hold the position of president and manage the direction of the company during the market downturn. This drove a concentration on optimization, strategic partnerships, and a shoring up of customer service action.

Shuck would stay in Williston and assist in establishing the Port of Vancouver, USA, there. He spearheaded the establishment of multiple economic development and supply chain relationships. These included connections between the international ports of the Pacific Northwest and the North Dakota energy and agricultural industries, resulting in the rise of the “Advantaged Supply Chain” and “Vancouver Energy Project” initiatives.

According to Shuck, the experience gained through his illustrious career provided insight into how wells should be managed from start to finish to produce oil and gas responsibly and not at the detriment of others or the land. Discovering that this was only sometimes the case, Shuck’s career would steer him toward taking action himself.

How Did They Fix That – Well Done Foundation from U.S. Energy Media on Vimeo.

The WDF Takes Shape

After witnessing that eye-opening 2019 summer with Kevin-Sunburst Oilfield, Shuck drew upon the need for immediate action and established the WDF as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. The group dedicated itself to plugging orphan wells left in poor condition, leaking harmful gases, and polluting the land.

“We are rigging up on our 40th well,” says Shuck, “and we have hundreds of wells ahead of us.”

Through the contributions made by corporate sponsors and the support of generous donations, the WDF has worked in multiple states and made a successful impact, plugging wells and permanently reducing harmful methane emissions by over 500,000 metric tons of CO2e. It has levied successful outcomes across Ohio, West Virginia, Oklahoma, Texas, Louisiana, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming and California.

For the WDF to move in and plug an abandoned or orphaned well, the organization must own it. Those donations and sponsorships prove critical in making this aspect a reality.

“It simply comes down to personal relationships,” says Shuck. “This is an opportunity to have an intersection between passion and purpose. If we can provide a platform for others to participate in this great work and inspire others to do this work, then we are winning at the game.”

How Did They Fix That – Well Done Foundation from U.S. Energy Media on Vimeo.

Implementing a Critical Process

The WDF subscribes to a critical process in closing out these problematic wells. With over 3.5 million orphaned wells across the United States that emit harmful methane gas, Shuck developed a successful strategy inspired by urgency.

To plug these troublesome wells, the WDF undergoes a detailed identification plan. Several sources are mustered first to identify the well, and thorough background research is performed. The data allows the WDF team to establish a well history and study its characteristics. The location is known, and surface ownership and existing leases are considered.

Working as a nonprofit and through sponsorships and donations, the WDF needs to carefully direct its funds. As a result, each orphaned or abandoned well has to qualify for its program. Through field verifications, an orphaned well must be qualified in order for the WDF to assume ownership. Working with surface owners, the WDF gains access to perform testing that includes greenhouse gas emissions, surface conditions, and accessibility. A report is generated, and the data is studied to determine if the well qualifies for the WDF assistance.

After qualification is determined, the orphaned well must be monitored and analyzed for a specific period. After a bond is posted, the well can be adopted from the state where the well is located. The WDF needs to move in to rectify the problem immediately. Instead, the organization establishes a budget and then implements a new orphaned well campaign to raise the funds required to close out the well.

If the well qualifies for special assistance, the WDF will implement its carbon finance strategy for the plugging stage of well rectification, which includes plugging, abandoning and restoring the surface area of the orphaned well.

“There aren’t enough federal dollars to plug and abandon these wells,” says Shuck, “[so] we developed a carbon credit program.”

According to Shuck, part of the WDF funding process includes his organization taking ownership of the carbon credits associated with the wells of which the WDF takes ownership. Like oil and gas companies, the WDF sells these credits and uses the profit made to fund the plugging and abandoning of these orphaned wells.

“Our funding strategy is managed well by well,” says Shuck.

After adopting the well and taking ownership, the WDF collaborates with the well location state to devise an approved plugging and abandoning procedure. Before action is taken, Shuck plans the work activities with the state and local entities and surface owners for complete transparency. While being a good steward of the environment, the WDF additionally supports the local economies where the orphaned wells are located by relying on local and regional service companies to perform the well work activities.

“After we take ownership of the well, we have 12 months to get it plugged,” says Shuck.

The WDF continues to work with state and local agencies during the restoration phase of plugging and abandoning orphaned wells. Together, they develop a long-term monitoring plan for the wellsite. Based on the American Carbon Registry protocol, the orphaned well campaign’s climate offset benefits are calculated and audited by an independent third-party validation group.

Reason for Responsibility

Determining if an orphan meets the WDF criteria well and implementing the adoption action is a detailed process. Partnering with this course of action will raise campaign funds, but bringing the dream to fruition is an expensive and monumental task. With such a grand effort exerted and money gathered and spent, one cannot help but ask why. If an oil and gas company contracts to drill the well and stands to benefit from whatever the production period might be, how does the oil and gas company walk away unscathed? One might also ask for justification as to why others should pay the bill to plug orphaned wells.

The reality is that well sites are not only found in remote areas far from society. They can be found on ranches with livestock grazing nearby. Well sites have even been set up in urban areas and residential neighborhoods. With what seems to be a high risk for a potential negative impact, Shuck explains how some oil and gas companies seemingly abandon wells when they are no longer financially viable.

“Each state is responsible for how these wells are managed,” says Shuck. “So, if an operating company has wells across multiple states, the requirements and enforcement of these wells will differ from state to state.”

While responsibility should be mandatory and enforced, the likelihood of orphaned wells falling out of sight, literally from overgrown surface areas, and a subscription to the “out-of-sight, out-of-mind” notion, the landowner is left picking up the pieces of neglect. Not only can the atmosphere become polluted from irresponsible emitting wells, but surface areas are also often left in disastrous conditions, decreasing the quality and value of the surrounding land and property.

Shuck adds that another piece to the puzzle should be considered. Although most would agree that people should be responsible for their problems, climate change is a genuine part of this equation. The money spent to plug emitting wells rids the atmosphere of harmful gases and assists in fighting climate change. According to the WDF website, the average cost to plug an orphaned well is approximately $65,000, with several wells emitting 4,000 metric tons of CO2e annually. Removing an equivalent calculation of harmful gases would require 400,000 trees to be planted and grown for 20 years. With the race to reduce the carbon footprint, the need to raise funds and deal with problematic wells is evident.

“We hope we are inspiring operators to do the right thing in the future,” says Shuck. “Our goal is to inspire and enable.”

Taking stock of the number of wells that the WDF has successfully mitigated and looking at what the future holds, Shuck maintains his organization will continue to offer this critical service in the coming years. After capping the well, service is ongoing to ensure successful results are not just obtained, but maintained.

“The measurement and monitoring piece is critical,” says Shuck.

After the WDF mobilizes from the well and moves onto the next project, its team returns to where the successful campaign occurred. Continuing to measure any potential gas release ensures that no harmful gases escape the wellbore and leach into the atmosphere.

The WDF subscribes to a detailed mitigation plan that requires a significant commitment from start to finish. Resources must be allocated and funded, planning and execution must be exacted, and fortitude must be had to see the process through to completion. Although science proves and justifies the need to plug orphaned and abandoned wells, a sense of what is morally correct drives Shuck’s passion.

“It doesn’t matter if you are a climate crusader or a climate denier; plugging these wells is the right thing to do.”

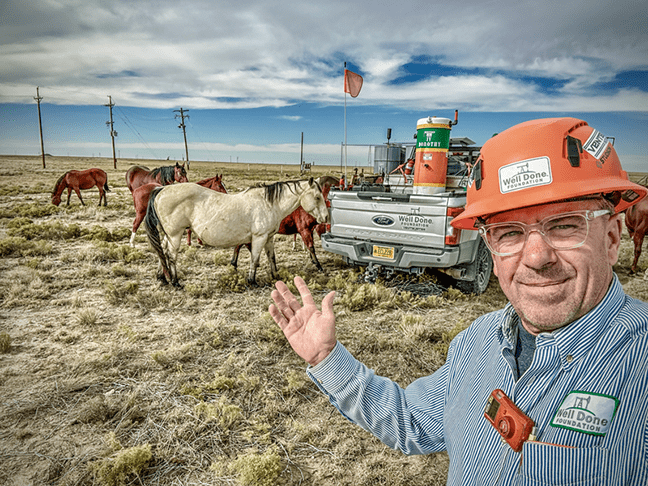

Headline photo: Curtis Shuck presenting another project in the Permian Basin in New Mexico.

Nick Vaccaro is a freelance writer and photographer. In addition to providing technical writing services, he is an HSE consultant in the oil and gas industry with twelve years of experience. Vaccaro also contributes to SHALE Oil and Gas Business Magazine, American Oil and Gas Investor, Oil and Gas Investor, Energies Magazine and Louisiana Sportsman Magazine. He has a BA in photojournalism from Loyola University and resides in the New Orleans area. Vaccaro can be reached at 985-966-0957 or nav@vaccarogroupllc.com.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.