Barnett: 2006

Trevor Rees-Jones, founder and CEO of Chief Oil & Gas, LLC: “As the Barnett progressed, we were always drawing these lines, projecting our fear of where it would stop. It was foreign – the nature of an unconventional play – to our thinking that ‘Hey, this thing can go on and on and on.’”

“We had a mindset based on conventional reservoirs and conventional exploration – always worried about where it was going to end. I felt a bit like Pavlov’s dog going through the oil and gas business in the first 15 years, drilling all those dry holes and having things not work out so much. I was always waiting for the next shock.”

“We were so attuned to the conventional, high-risk nature of exploration at the time that it was hard for us to grasp what was happening in the early years of the development of the Barnett.”

Chief made its Jarvis-Chief 1 in 2002 three miles south of the dozen wells that had completed in northern Tarrant County. “[George] Mitchell had developed this numerical calculation to indicate whether you had a good well. Our well calculated very well and we brought it on production at 1,000,000 cubic feet a day. That advanced the field three miles south and we had a ton of acreage between and around that.”

“That was pretty phenomenal to us.”

“As we established production miles away, it was kind of bewildering that this thing could really be this big. When I realized this was really something different was when the larger companies – XTO, Chesapeake and the others – wanted to get involved. I remember when Bob Simpson (XTO chairman and chief executive) paid a visit to me and inquired as to whether we were for sale. At the time we were not this was early ‘05. Chesapeake made its first acquisition (after its inheritance from Canaan’s portfolio) in late ‘04 in Johnson County.”

“When these companies began to get involved that was telling us: We’ve really got something here.”

Eagle Ford: 2008

Dick Stoneburner [then-president and COO of Petrohawk Energy Corp.]: “Sitting in a Weber Energy office in Dallas with [Charles] Cusack, [Jana] Beeson and Sonny Tuttle, another Petrohawk geologist, we looked at the data for about 10 minutes, saw the production, saw the logs, saw the core, saw everything. I said, ‘We gotta buy this.’”

“I walked into Ben [Weber]’s office and offered him $3,000 in acre with no authority whatsoever. Floyd [Wilson, Petrohawk CEO] certainly didn’t know this.”

“You know, that’s just how flat we were as an organization and how quickly we made decisions. If I had walked out of that office and we had postponed it for another month, there’s no telling what it might have cost, or he might have sold it to someone else. I got his attention at $3,000 an acre, which was a fair price.”

The leasehold was in the super NGL rich window of the Eagle Ford. “We ended up buying an area that people have paid $40,000 an acre or more four since then. It is the best part of the play, bar none.”

Steve Herod says, “People probably thought that $3,000 an acre was over the top, but we thought it was a terrific deal. As it turned out, it was. It was hugely economic.”

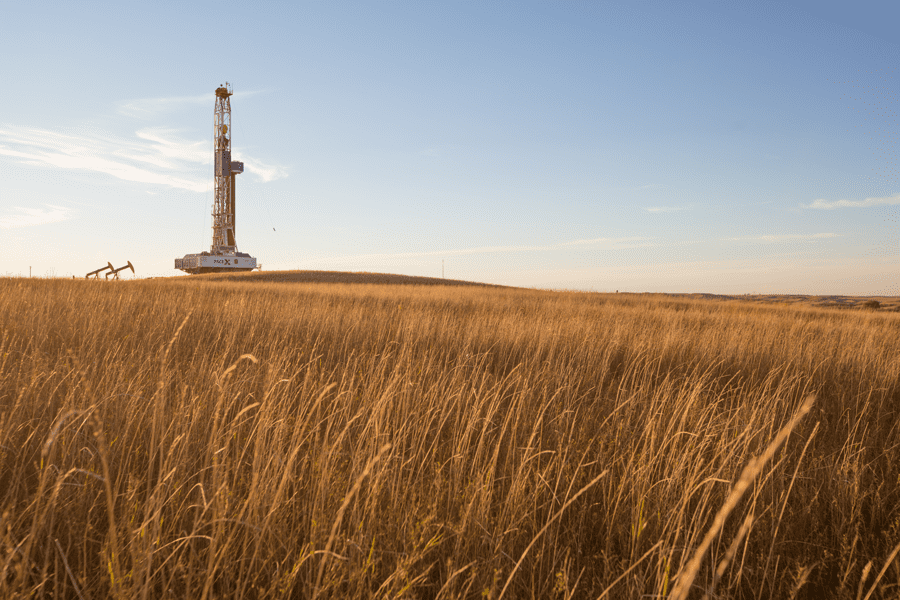

Bakken: 2014

When joining Enerplus in the Bakken in Montana in early 2006, [Ward] Polzin didn’t see yet what the Bakken would become. “That was really the first unconventional oil play,” Polzin says. “It was pre-Barnett really. Lyco (in 2000) was the first to put in a fraced horizontal of scale in oil-bearing, tight rock. I think we saw that horizontal fracs of scale could change things.”

“But we hadn’t seen the evolution yet. Elm Coulee Field, obviously, was a sleeping giant. The porosity was much better in that area, so it had a kind of conventional aspect to it. It was tighter than anything we had ever done, but it wasn’t as tight as in North Dakota.”

“We could apply this horizontal frac into tighter rock and make it work. ‘But, man, I don’t know if it’ll work in North Dakota because it’s really tight over there.’ That was the thinking at the time. We (at Enerplus) drilled some North Dakota wells in the early days right there with Harold Hamm.”

“But, boy, he had the vision and much better than we did. We were different, too; Enerplus was still a royalty trust. We couldn’t take that kind of risk.”

He credits EOG with finding the enormous Parshall Field, “but that was geologically unique. I give them credit for what they do so well – finding the sweet spot of the sweet spot. No doubt they did. But in terms of making this ubiquitous – making it work almost everywhere – Continental deserves that credit.”

Note from the author:

U.S. gas production has grown to exceed more than 90 Bcf/d this century from an anemic, decades-long output of some 50 Bcf/d, according to the Energy Information Administration

(EIA). In addition, the Agency says U.S. oil production reversed its deep dive from nearly 10 MMbbl/d in 1971 to some five million, topping off at nearly 13 million in early 2020 – a rate only upended by a global pandemic.

Previously a net importer of some 12 Bcf/d of natgas, the U.S. now exports nearly 20 Bcf/d via pipeline to Mexico and by LNG tankers to Europe and Asia. It’s a net exporter today of some 12.4 Bcf/d, according to EIA figures.

U.S. natural gas prices regularly exceeded $6 an Mcf during the aughts and collapsed to a couple of bucks with the addition of production from the Marcellus and Haynesville in the 2010s.

As industry has responded with newbuild export pipe and LNG export facilities, while powergen and manufacturing have switched to greater use of natural gas, prices have corrected this year (2021) to reflect the new, tightened market. U.S. shale gas producers are seeing $5 an Mcf for their products. This is while the surviving producers had beaten back costs to less than $2 to survive a persistent strip of less than $3 an Mcf.

Contributing to the tightened market has been reduced associated gas production from the Permian Basin and other oil-focused plays, as operators there mostly suspended new-drill activity in 2020 in response to the oil-price collapse.

Into 2021, with oil at more than $70/bbl again, U.S. oil producers are not restoring drilling levels to that of pre-2020. According to Enverus, rig counts remain between half to two-thirds that of the pre-2020 level in the Permian, Bakken, Eagle Ford, Denver-Julesburg (DJ), and offshore. In the Permian, in particular, operators are running out of drilled but uncompleted wells (DUCs).

Meanwhile, the Anadarko Basin, which has a bounty of gas and NGLs in addition to oil and was already struggling with low gas and NGL prices before 2020, has picked up rigs.

The Appalachian count remains sideways at about 45 due primarily to constrained takeaway for the more than 30 Bcf/d rather than due to poor prices.

The only play, other than the Anadarko, with a greater rig count today than pre-2020 is the Haynesville, with its direct connections to Gulf Coast LNG plants and other markets.

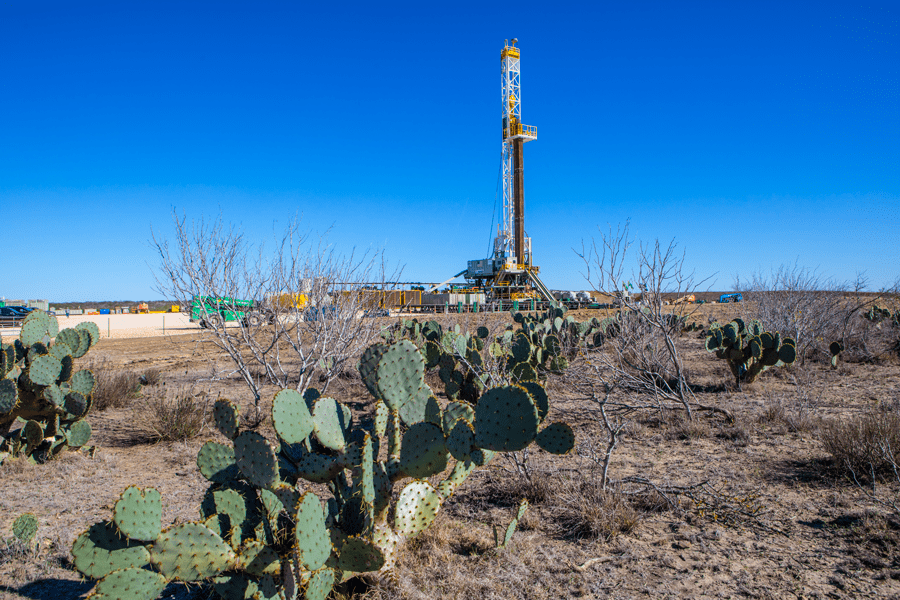

Headline photo courtesy of Marc Morrison ©2021 – www.marcmorrison.com. The Eagle Ford Shale.

Nissa Darbonne, author of The American Shales, is editor-at-large for Hart Energy Publishing, LLP. She began her journalism career in 1984 in the oil and gas fields of South Louisiana, including for The Daily Advertiser (Lafayette) and The Morning Advocate (Baton Rouge). She received her B.A. in English and Journalism from the University of Southwestern Louisiana (University of Louisiana at Lafayette). She lives in Houston.

To read more of Nissa Darbonne’s commentary on U.S. shale plays, see her article on the Marcellus in the Sept/Oct 2021 issue of Oilwoman Magazine.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.