“We don’t receive wisdom; we must discover it for ourselves after a journey that no one can take for us or spare us.” – Marcel Proust

“Our industry has ventured out onto a new frontier. We are moving at a faster and faster pace. The information age, as this generation calls it, is pushing technology in ways that years ago we could only imagine. Unfortunately, with all of our success, it generally is our failures that teach us the “best.” Our successes tend to make us think we are fireproof; our failures bring us back to earth and back to the drawing board. I only wish this one would not have been as bad, but many good things will come out of it, at a very tough cost.

The Deepwater Horizon/Macondo incident was our Apollo One. We cannot afford a Challenger to follow.

In 2013, I was at the crossroads of my life in this industry.

The son of a Hughes Tool Company drill bit salesman, I grew up thinking that every kid went to the rig on Christmas day to drop off bits. My time growing up was spent with my dad, driving across the southeastern U.S., watching the rigs come and go. Graduating from high school a year early due to another transfer, I continued to Mississippi State, not because it was the best, but because it was the nearest and offered an education that could not be obtained in South Mississippi.

Struggling through college, it was the oilfield that kept me interested in continuing that education. First with Zapata Offshore, then with H&P, working on the drill floor. I found my home with Union Oil of California while continuing my education. After being awarded a petroleum engineering degree in 1982, and having a young family, I journeyed home to Lafayette where Mom and Dad had originally started. The lesson that the oilfield had burned into my mind was a simple one, “Can’t Do, Can’t Stay,” meaning if you can’t do the job, you’re out. First heard at the age of 18, it has continued to drive me to this day.

Originally trained in reservoir, then onshore production, my final point of training with UNOCAL was drilling and completing high-pressure wells. I was overjoyed with the position as an engineer in that department. Less than two months later, I was thrown to the wolves. I had my first rig and was left “alone” as the drilling foreman. In those days, it was sink or swim. I learned when I had a question for which I had no answer, I called my other family – the drilling foremen on the nearby offshore rigs. They became my family away from home. My heroes who looked after me as I sailed on this new ship of opportunity. I could not have been in a better place to learn.

Ten months after being in the department, having just become a daddy for the second time, I returned offshore for my weekly tour. This time found me, instead of at home on Thanksgiving night with my family, on a Bethlehem jackup MODU, for I had learned that some of us are just born to be sailors. Not that we did not want to be home, but the calling for adventure and the sunrises and the sunsets on the water could only begin to fill our sails.

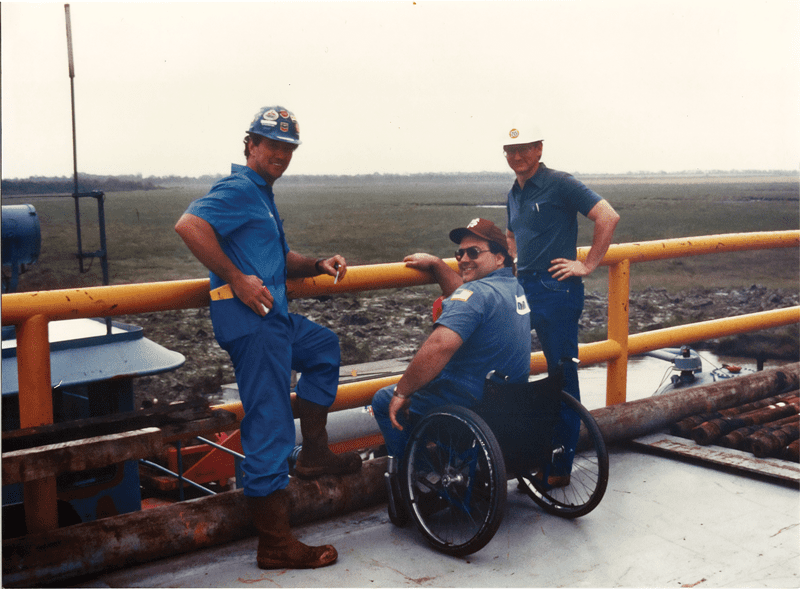

That Thanksgiving night on November 22, 1984, started my real journey in this oilfield. On the rig floor with my crew, pulling apart a well, a pup joint parted. The resulting crash killed the floor hand holding the flashlight for me and paralyzed me from the waist down.”

Farmer was rushed to a hospital in Lafayette, where they were able to save his life. He was then transferred to a rehabilitation hospital in Houston, Texas, where he attempted to learn to stand and walk again. Even though he had spent years working on the drilling floor, nothing could have prepared him for the hard labor of physical therapy. Unocal installed a WATS landline, so he could take the calls from the offshore rigs and ask them about their drilling problems. And advise them on their drilling problems. As months of physical therapy passed, he kept holding the vision of walking again and being free from his wheelchair. His doctors and therapists taught him to adapt his car so he could drive independently. Ultimately, it became clear to him and his medical team that he was not going to walk again.

Back in Lafayette nearly two years later, Rick fell into a deep depression and anger at God and himself for failing to spot the faulty corroded pup joint that killed his floor hand and left him unable to walk.

His drilling family held an intervention and talked him into entering a 30-day addiction program. He explained to them that he was not actually addicted. He did not want to conduct his life confined to a wheelchair. He recalls being furious when he entered the program. But on Day 20 Ricks says he heard the voice of God asking him, “What made you different?”

He completed the program determined to prove that God could help him do the impossible. It was the definitive day that changed his life. This is the verse of scripture Rick uses every day as he faces the challenges of life in a wheelchair:

Philippians 4:13: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.”

“I wondered for a long time how good could come out of that. But, strangely enough, in God’s wisdom, all things seem to work out for the best for some. And, so, my journey did not end, but merely started.

April 20, 2010: The night of the Deepwater Horizon deeply impacted my family again. The little baby who was 10 days old when I was crippled was now a grown woman. She had been a bridesmaid the previous year at the wedding of Dewey Revette’s daughter. (Revette was the Transocean driller who died the night the Macondo well blew out.) That young lady had called my daughter and asked if I (her daddy) could find out anything about her daddy. When I got that phone call from a sobbing daughter, I answered that I only knew what I was hearing over the television. I knew better than to call my friends with Transocean (once Transworld and Reading and Bates); we all knew it was going to be bad.

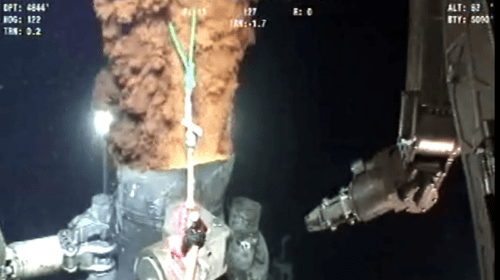

While in Starkville, Mississippi, a week later for that daughter’s graduation from grad school, I received a call from a diving company at 4 .am. I was asked if I could talk to a “friend” from the Navy, who was under orders by the President to begin moving equipment to the Mississippi Canyon 252. The Commander asked what the Navy could bring to staunch the gushing well. I explained that the military does not have any equipment that could even light up the blow out preventer (BOP) in 5,000 feet of water. The extremely high pressure at that depth and freezing water temperature would crush a submarine instantly. I explained that, even if the military could light up the bottom of the seabed, the military has no equipment or the complex deepwater engineering that could stop the gusher. Only the remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) could splash down and light up the broken wellhead and BOP.

Even our own industry had no clue at that time. It was a problem that the best and brightest had denied could ever happen. Again, so did those engineers with the Apollo One command module. During the 87-day gusher, deepwater drilling and production engineers from dozens of operators were included on the open phone line as bp, Transocean and Halliburton listened to added advice.

In 2013, I was haunted by the question, “What can I do to help our younger crew not make our mistakes?”

Three years after the Macondo blowout and having read millions of pages of trial documents just made public in spring of 2013 during Phase one of the Civil Trial, AND knowing families of those who died and survivors and perhaps experiencing Macondo through the lens of my 1984 accident, I slowly realized God had something else for me to do in this industry. I resigned from my drilling manager position to begin teaching a night class on Monday at the University of New Orleans to a new post-Macondo generation of drilling engineers who had never had an opportunity to work summers on a drilling rig. I also enrolled at LSU for a short time to see if I needed a master’s or PhD.

But, then, in 2013, the U.S. Department of the Interior announced the new federal regulations which called for a licensed engineer to sign off on every aspect of deepwater drilling in federal waters in the U.S. I realized that if I could pass the Professional Engineering License Exam, I would have the opportunity to help design and execute Macondo type wells and work in a new leadership position in our industry’s professional societies. Proving I could pass the exam would not earn me extra money but, if I could pass it after being out of school over 30 years, I could encourage the younger engineers as well as industry leaders my age to pursue the license for ‘the good and protection of society.’”

Preparation for Fundamental Elements (FE) requires 250 to 300 hours of studying every type of engineering: electrical, chemical, mechanical, civil and nuclear. Taking the Professional Engineering (PE) License Exam requires the same number of hours, and much more study time than getting a master’s or doctoral degree.”

Engineers’ Creed (1954 Original Version)

As a Professional Engineer, I dedicate my professional knowledge and skill to the advancement and betterment of human welfare.

I pledge:

- To give the utmost of performance;

- To participate in none but honest enterprise;

- To live and work according to the laws of man and the highest standards of professional conduct;

- To place service before profit, the honor and standing of the profession before personal advantage, and the public welfare above all other considerations.

In humility and with need for Divine Guidance, I make this pledge.

“I have felt that in order to “train” our engineers, it was necessary at times to bring them to a burn ward of a large hospital. To emblaze in their minds that failure is not an option in our industry. Knowing that a man died next to me, while he trusted me to bring him home safely, has haunted me to this day. Those that were involved in the Deepwater Horizon/Macondo incident will be haunted by their demons every year on April 20th for the rest of their lives. I remind my students that an engineering degree is not a license to kill, and that it should be taken seriously. People really do trust us, whether in the oilfield, or riding over our bridges, driving down our roads or working with our machinery. This is why we must continue to learn from our mistakes and not repeat them.”

***

Warren “Rick” Farmer, IV, grew up the son of a former USMC and Air Force man. After serving his country, his father began selling drill bits for Hughes and delivering bits directly to the drilling rigs as they needed them. By the time his father retired as the U.S. Vice President of Hugh Tool Company, he had 48 percent of the bit business in the U.S.

Farmer has spent the last six years using his Professional Engineering License to help offshore companies like Stone, Cox and Beacon Offshore Exploration design and execute many of the complex high temp and high-pressure wells in such a way that will prevent another Macondo type disaster.

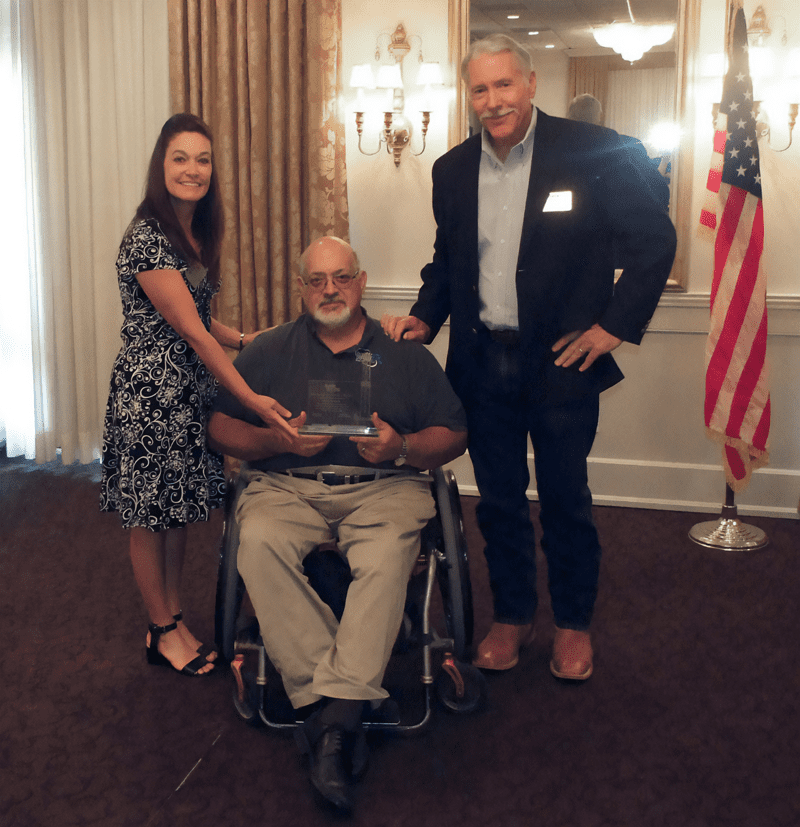

Farmer has served on the National Board of the AADE (American Association of Drilling Engineers) as President and as Vice President. He has served on the boards of the Society of Petroleum Engineers for the Delta and Evangeline sections and chaired the SPE sections in New Orleans, the Delta section and the Evangeline Section. He chaired the Deepwater Symposium Drilling Section in New Orleans from 2012 to 2023.

Farmer helped obtain thousands of dollars of lab equipment for Nicholls State, LSU, Mississippi State and the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. He has served in a leadership role in responding to a BSEE/USCG Spill Response Test Response. He also assisted the International Steering Committee of the National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine Gulf Research Project in finding certified offshore workers to participate in the January 2018 Workshop in Houston.

Among his honors, Farmer was chosen as a Distinguished Fellow of the Mississippi State University Bagley College of Engineering for 2010 for the Petroleum Engineering Department. In 2013, API honored him with the Meritorious Service Award from the Delta Chapter of the American Petroleum Institute. In 2019, he received the National AADE Meritorious Service Award from the New Orleans and Lafayette Chapters of AADE presented to that member of the AADE whose contributions are considered significant toward the advancement of the Association and the accomplishment of its goal. In 2022, he received the National AADE Outstanding Service Award in recognition of continuous, long-term contributions toward the advancement of the AADE and the accomplishment of its mission.

In June 2023, the University of Louisiana at Lafayette hired Farmer to teach five courses in petroleum engineering for the fall and spring semester. For Farmer, this assignment means more than all the awards he ever received. This provides him with the opportunity to mentor the next generation of engineers and young professionals. These students will be a part of his life permanently.

Lillian Espinoza-Gala, owner LEG Exploration Education, served on the steering committee for National Academy of Science Offshore Worker Empowerment workshop held in Houston in January 2018 and a section of her Macondo Research is published in Chapter 2 of the proceedings. She currently serves as a Membership Chair on SPE International Human Factors Technical Section Board.

Lillian Espinoza-Gala, owner LEG Exploration Education, served on the steering committee for National Academy of Science Offshore Worker Empowerment workshop held in Houston in January 2018 and a section of her Macondo Research is published in Chapter 2 of the proceedings. She currently serves as a Membership Chair on SPE International Human Factors Technical Section Board.

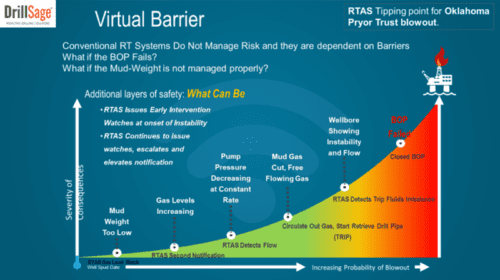

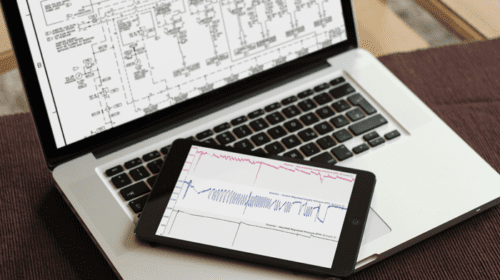

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.