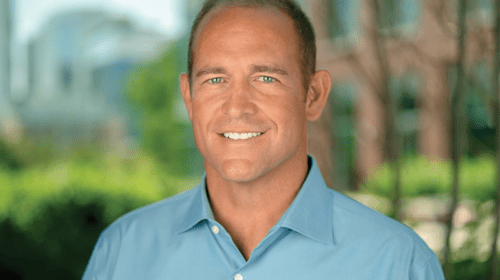

Engineers design and build things, and they are driven to make them better. Dave Payne can speak in very complex, technical terms about the engineering side of the oil and gas industry, but there is a recurring theme that runs throughout the conversation about his 41-year career, and that is building a better industry by creating a more diverse and equitable workforce. Maybe that is one of the gifts that this industry has given him – the ability to see the value in other people who are different than he is and to recognize that those differences are precisely what will transform the industry.

Payne graduated from Penn State (’81) with a degree in petroleum and natural gas engineering, but no grand plan for his career. Education and opportunity, aptitude and maybe a little good fortune converged to open the doors to his first job at Getty Oil – a name synonymous with the petroleum industry.

He spent three years there, in a small California office, with only six other engineers, but says, “It was a great place to start because you had a lot more responsibility than you’d get in a bigger operation. Because it was small, Getty tended to empower its employees to make decisions.” Even then, there was something that struck him – “It was all white men. The only women in the office were the admins and a couple of technicians.”

Aside from the obvious lack of diversity, there were other things that were missing, such as the benefits of mentoring, which may have been somewhat of a foreign concept 40 years ago. “When I started getting into drilling, there was nobody that had any drilling experience at all,” Payne says. “I really had to learn on my own, which comes with its own set of challenges but, at the same time, because you don’t have anybody to lean on, there’s a very steep learning curve.”

While he may not have recognized it at the time, diversity and mentoring would become central to his career and Payne would go on to use the platform his privilege afforded him to help bring others, who didn’t have the same privilege, up through the ranks.

But, first, he had to get there himself, and, as he says, it was a “convoluted path” to Chevron. While still at Getty in the mid-80s, Payne says, “As we were watching all the other mergers happen around that time, [our attitude was], “We’ll be fine; nobody is going to buy us,” but when the Getty family put its stock on offer, “That was the end of it.”

In 1984, Texaco made a $10 billion dollar offer to buy Getty, in what was then the largest merger ever, eclipsing the Du Pont Company’s $8 billion purchase of Conoco Inc. in 1981. (Texaco would go on to be tied up in court for years – and eventually declare bankruptcy – over litigation with Pennzoil, which had also made an offer for Getty, but by then Payne had moved on.)

Despite not having a master plan for his career, he did know one thing: He wanted to work internationally. Before leaving Texaco, he had put in for a number of overseas assignments, not landing any of them initially due to lack of experience. He applied for a position with Caltex (now owned by Chevron). “Didn’t get it.” He put his name in for a job in Kuwait. “Didn’t get it.” In hindsight, he says that may have been a blessing in disguise, as many oil field workers later ended up in Baghdad during the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

Some years later, Payne discovered that two weeks after he left Texaco, his former employer went looking for him to offer him a position he had applied for in Copenhagen. “Who knows where my career would have gone if that would have happened?” he asks rhetorically. “That could have derailed everything and then I would have had different experiences.”

Instead of Denmark, he went to work for an independent where, instead of seven engineers like there had been at Getty, there were a total of seven employees, including the two owners, who ran out of money nine months later. “Raising money and investing it in wells is a pretty rough part of the business,” Payne observes.

The loss of that job led him to consulting and, despite the downturn in the late ‘80s, Payne says he never went a day without work. It came at a price, though, as he and his wife, Letitia, had three small children at home. Seeking stability for his young family, he took an opening with Unocal in 1990, and would remain with the company for 15 years. That decision enabled him to attain his goal of working internationally, during which time he gained a greater appreciation for other cultures, and saw firsthand how diversity could benefit and strengthen workplace culture.

“From a leadership perspective, working overseas is extremely valuable, and I don’t think that’s unique to energy,” Payne says. “If you take it seriously, and really try to engage and figure out how to best connect with the people in these different cultures, you gain a lot of perspective. You learn to adjust your style to get better outcomes.”

Accepting assignments in Trinidad and Tobago, Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand afforded his children the opportunity to grow up as expatriates and be exposed to the diversity of other cultures and worldviews, something he believes enriched them as a family.

Payne was working in Thailand as a drilling manager when Chevron bought Unocal in 2005, which is how his “convoluted” career path led him to Chevron, where he rose to become vice president of drilling and completions and, in 2018, assumed his current role as vice president of health, safety and environment (HSE).

Those 15 years abroad had a profound effect, not only on Payne personally, but on his leadership style. They heightened his awareness of the inequities that exist within the industry and what he could do to influence change.

“When I came into the industry, it was basically all white males and it was very rare to see women or people of color. You’d see women occasionally – a female engineer or geologist – but if you were out on location, it was very, very rare.” Payne recognizes that change has been slow, but says the industry’s focus was what had to change. “It started with saying that we needed to hire more diverse individuals, so we hired more diverse individuals. But if you don’t change [the culture], you can only make small inroads. I’ve had to go through this transition myself. I can’t claim to have known 30 years ago what I know now,” he acknowledges. “I wish I would have, but that’s not how the world works.”

He says there came a realization that it was not enough just to hire diverse individuals and leave them to fend for themselves as part of the non-dominant culture. “We started to help these diverse candidates learn how to navigate people like me,” he says bluntly, referring to his white male cohorts in positions of leadership, “and that was a big step for us, because we had given them tools to be able to survive. Now we’ve made a shift.”

“We shouldn’t be teaching them to navigate us; we have to change because simply navigating us isn’t going to get us to where we want to be. And that’s where the hard work is happening today – creating real safe spaces for diverse candidates.”

Payne admits that early on, in an effort to help bring more diversity to the workforce, he would hire several women or African Americans, but then assign them to different rigs, ultimately leaving them isolated and alone. Calling it a “big mistake” and saying he would never do that again, he adds, “Now, if you hire four women – or [other minorities] – you put them in the same place. At a minimum, you would make sure there’s always at least two online, so they have support.”

Just as the industry made that first shift in focus to start moving toward a more equitable workforce, now Payne says the questions that have to be asked are: What do we want in our male leaders? What are the behaviors we expect of them to allow us to have a more diverse workforce?

Perhaps because retirement is looming on the horizon, he feels emboldened to speak freely, but Payne, who is known in the industry as a straight shooter – sometimes to his detriment – is blunt in his assessment. “It is straight white men that make the difference. We make all the decisions; we have the power – let’s make no mistake about it.”

Using the right to vote and marriage equality as examples, Payne says women and Blacks didn’t get the right to vote, and gays didn’t get the right to marry, because they wanted it; they had always wanted it. They got the right to vote and the right to marry because straight white men decided they could. “Change is going to happen in the oil and gas industry when white men like me make conscious decisions that it’s going to change – and so we have. Whether [people] like it or not, that’s the reality on the ground. And, so, we have a role to play.”

That responsibility entails being confident of the intentions of others that are placed in positions of leadership. Payne says he has had conversations with people in the workforce who have decided to move on because they haven’t been allowed to be successful and ultimately decide it’s not worth the struggle – and that is the industry’s loss. “It’s not always intentional; they don’t recognize their unconscious biases.”

A leader’s influence is felt not only in the work environment but outside of it, where relationships are formed, and access to mentors or sponsors is sometimes made available. As drilling manager in Thailand, Payne remembers playing golf and says, “When I think back, it was always a bunch of white guys; there were no women. The white men got access that other people didn’t. I was creating a bias and I didn’t even recognize it at that time,” he confesses. “I would never do that today.”

Payne believes the next phase in transforming the industry is for energy companies to bring along their business partners that understand the benefits of having a diverse workforce. However, he says it is critical that they are clear about Chevron’s expectations; otherwise, they have the ability to undermine the progress that has been made.

Conceding that a “boys will be boys” mentality and locker room environment still exist on some locations, Payne says, “It’s not okay. It’s never been okay, but we didn’t do anything about it and [there’s an attitude] – they’re field guys, it’s their rig, this is the way it is, it’s just part of the culture. It doesn’t have to be part of the culture and it wouldn’t be part of the culture if we didn’t allow it to be.”

Payne sees a big opportunity in oil and gas for a shift in that area, particularly in field operations. “The closer you get to operations, the less diverse oil and gas becomes, particularly at leadership levels. We have a lot of people who have carried wrenches who are very diverse,” Payne says, “but, when it comes to who’s in charge, it’s not very diverse the closer you get to the steel.”

As part of its diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) goals, Chevron is one of the energy companies that has partnered with Catalyst in the Men Advocating Real Change (MARC) program (www.catalyst.org/marc).

In order to build the workforce of the future, the industry must first attract those diverse candidates from all walks of life and, the deeper we get into the energy transition, the more crucial it becomes to convince the up-and-coming generation that degrees like petroleum engineering lead to a viable career path.

In January 2021, the New York Times published an article about the diminishing prospects for petroleum engineering majors and graduates, with one of the interviewees calling the industry downturn and move toward renewable energy “a slap in the face… that rocked our entire mind-set.” Payne, who holds a bachelor’s in petroleum and natural gas engineering, and whose daughter, Danielle, followed him into the industry with a degree in petroleum engineering from his alma mater Penn State, sees the situation with the clear-eyed view of a 41-year veteran who has survived the vagaries of the industry.

“If you look at any estimate of the energy mix as far out as 2050, oil and gas still plays a pretty significant role. You’re going to see some increase in gas but, even if oil were to decline at five or 10 percent a year in total use, you still need to replace the decline curves. For fields around the world, there’s a continuous amount of work that has to be done to backfill underneath that curve, and so even the most optimistic energy transition estimates still have oil and gas in the mix in 2050.”

Payne says there is another dimension that he finds quite interesting. “Petroleum and natural gas engineers study fluid flow through porous media. So, if you’re going to do carbon capture and sequestration (CCS), if you’re going to put CO2 underground and store it indefinitely, [those are] the exact same skill sets that we use to get oil and gas out of the ground. Some of the enhanced geothermal, where we would pump cold water into the ground, allow it to heat up, and then recover it and use that waste heat for electricity generation would require the same skills that a petroleum engineer would have. It may take a little imagination, but there are tremendous opportunities out there.”

As Chevron’s executive sponsor for Penn State, that is exactly what he tells the students he talks to. He advises them to think about the future and the areas where they can be successful. Chevron’s recent donation toward the purchase of lab equipment will help Penn State’s petroleum and natural gas engineering department with its research on carbon capture and sequestration. “There’s a future there,” Payne says. “There’s a lot to be done.”

However, he points to the fact that governments are coming to the realization that they can’t just make the leap to renewables overnight because renewables at scale bring their own environmental concerns. They also have issues that require support that isn’t available without conventional energy generation.

“You still need a different type of energy before you’re going to be able to make that happen. There are still a lot of challenges that have to [be addressed] without bankrupting the world with energy costs. There’s a role for hydrocarbons, and I think carbon capture and sequestration are going to play a major role in the future.”

If the last three and a half years as Chevron’s VP of health, safety and environment (HSE) have taught him anything, it is that we will be more successful at making the transition and addressing climate change challenges if we work together. However, if the environmental community continues to demonize the petroleum industry and oil and gas keep “stiff arming” the environmental community, he is convinced that is not going to get us where we need to be. “It’s really going to require partnerships and they are very difficult to build because there are different perspectives. But, without those partnerships, we’re going to struggle to achieve the targets that have been set.” Governments may come together and make agreements but, as Payne puts it succinctly, “We’re the ones that have to execute those agreements.”

In April, Payne will hand off his HSE mantle to his replacement. In what must seem like validation of his efforts to create a more diverse, equitable and inclusive culture at Chevron – work he says comes with an “emotional toll” – his successor, Marissa Badenhorst, is an openly gay woman.

“I’m so proud of her selection because she’s focused on the frontline workforce. She’s really committed to some of the same things that I’m committed to and she can help push our culture forward in a positive way.” It is only natural that Payne would want someone to carry on the legacy he has created, although he says that is something that can’t be measured for at least a decade.

When he puts someone in a leadership role, Payne often startles them by advising them to start thinking about an exit strategy. He asks what they want to be remembered for when they leave the job. What do they want to leave behind? What do they want their legacy to be? He tells them to start building it now or it will be defined for them: “Control your own legacy.”

It is certainly a philosophy he has employed in his own life. Why leave now? “It’s just time,” Payne says resolutely. He is honest about how exhausting the last few years, leading Chevron’s pandemic response, have been. This past summer, he and his wife, Letitia, took a two-week road trip in an RV. Normally, he says he would have been “chomping at the bit to get back to work,” but when that Monday came, he knew.

Payne can leave Chevron with the confidence that he made a difference. “I helped make a big shift toward diversity and inclusion, and helped change the culture to really focus on working as a team and driving performance. Those are legacies I’m really proud of.”

While he doesn’t claim complete credit, Payne knows he was also instrumental in helping the company move away from a punitive response to safety violations and into a learning mode where the voice at the front line is heard. “We’re really engaged with our workforce now in helping us improve. It’s going to save lives. It’s going to make the business better, too, by being able to influence a lot of other companies to do similar things.”

It is evident from the respect Payne receives from his peers that he has left a lasting impression on the industry, but he sees the people he has had an impact on as his biggest contribution. “My focus has always been helping other people be successful and it’s paid huge dividends for me. Those people will outlast me and, hopefully, they’ll continue to pay it forward. And, if they do, then the legacy will just continue to grow and grow.”

The first thing I want to do when I retire is… go fishing.

My greatest indulgence will be… spending time with my grandchildren.

Something I didn’t have time to do while I was working but can’t wait to do now is… stand up paddle board.

Something I never want to do again is… pay administration.

The first thing I’m going to read is… Union by Colin Woodard.

I want to binge watch… not my thing.

Now that it’s safer to travel, the first post-retirement trip I’m going to take will be to… New England.

When I told my wife I was going to retire, her reaction was… “It’s about time.”

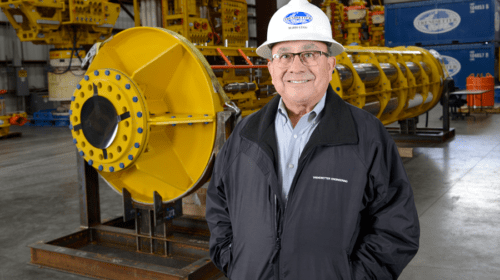

Headline photo: Dave Payne, then Chevron’s VP of drilling and completions, on a Transocean drillship (2016).

Rebecca Ponton has been a journalist for 25+ years and is also a petroleum landman. Her book, Breaking the GAS Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (Modern History Press), was released in May 2019. For more info, go to www.breakingthegasceiling.com.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.