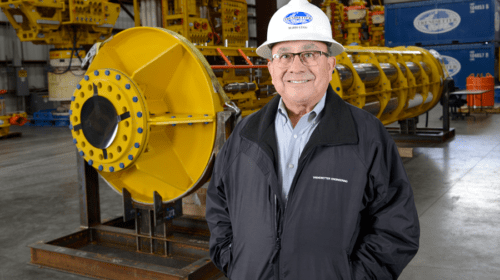

Among the characteristics a company looks for in a CEO or board member, diplomacy would be somewhere at the top of the list. Gaurdie Banister, Jr., the former CEO of Aera Energy, and a board member many times over – Marathon Oil, Tyson Foods, Dow and Russell Reynolds, to name a few – possesses that gift.

In fact, apparently, he is so diplomatic that when he has had to “chew out” an employee, he has been told it was the best reprimand they have ever received. “I do have this ability to have a conversation with people in a way that’s constructive and productive and doesn’t offend,” he acknowledges, in the thoughtful, measured way he has of speaking.

“I wanted to turn Aera into the Google of the oil field. I wanted it to be a place where everybody wanted to work.”

It may have something to do with treating others the way they would like to be treated (the opposite of the Golden Rule). The oil and gas industry came close to losing Banister before his career had really gotten started, and what a loss it would have been. Having joined Shell Oil fresh out of college in 1980 with a degree in metallurgical engineering from the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Banister recalls walking down the halls at One Shell Square in New Orleans six months into the job.

“I had an inside office like all new hires – not one with a window – but I had my office, and I had on a tie and a dress shirt, and somebody walked up to me and asked me to carry their mail…because they just couldn’t imagine that I was a Black engineer,” he says matter-of-factly. “I said, ‘No, I’m not carrying your mail; I’m an engineer here.’” His straightforward response belied how appalled he was at the request, which he viewed as a manifestation of racism. “I almost quit.”

After consulting his parents and doing some soul searching – “I asked myself, ‘Is this really a place I want to be?’ – Banister made the decision to stay. “I really enjoyed the work and the level of responsibility I had out of the gate. I also realized the grass would not be greener elsewhere.”

While he would experience “subtler aspects of racism,” he was armed with things no one could take away from him – his faith, education, work ethic and, along with it, a strong technical background. “I had technical credibility and that went a long way to me getting off to a good start, and how you start has so much to do with whether you’re going to be successful in any organization.”

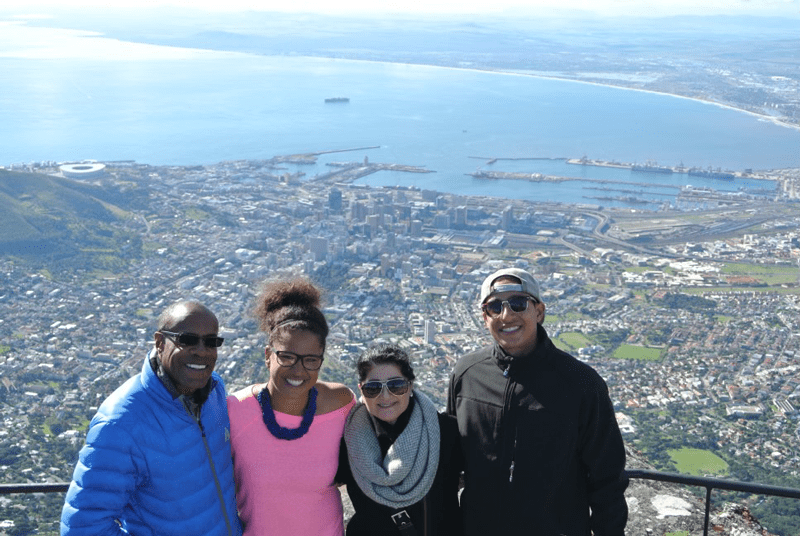

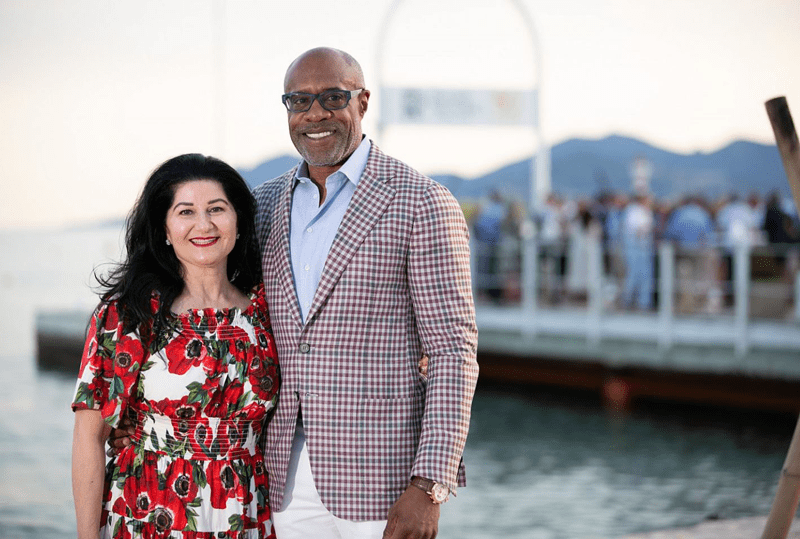

In discussing the keys to the success of his 40-year career in the oil and gas industry, Banister believes his academic background was critical, but he wants to start with crediting his wife, Simin, whom he married in 1981 and calls the love of his life. “She’s been my life partner. She – and my family and the people around me – has provided terrific support and strength for me throughout this journey.”

While Banister never uses the word “intentional” during our conversation, he decided to work within the system to achieve his career goals. When he was told after five years that, in order to progress, he needed to move from New Orleans to Bakersfield, California, he was willing to do so – without a promotion. After working his way through first level operations supervisor and first level engineering technical supervisor roles and into middle management, he was then asked to move to Houston – again, without a promotion – he says laughing, reflecting that it wasn’t very amusing at the time.

There, he went into what he calls a “meat grinder role” in the corporate office where he says he was “sprinkled with holy water.” That led to a senior level promotion in the offshore division as an asset manager in the Gulf of Mexico. Later he moved from the shallow water to the high-profile emerging deepwater division, “which was a really big deal.”

By mid-1996, Banister was Shell’s representative when CNN sent a crew offshore to cover the start of production from Mars, a Shell operated industry leading deepwater drilling and production tension-leg oil platform (TLP). “It was an amazing time to be a part of Shell,” Banister says with just a hint of nostalgia. “I later found out that there were people overseas in Royal Dutch Shell who had seen that coverage. I had absolutely no idea that piece went worldwide.”

Acknowledging that his rise through the ranks was facilitated by sponsors, he says, “You can move up without a mentor. I don’t feel like I ever had anybody in Shell who was quote/unquote a mentor – somebody who I would confide in, who I talked to about my problems – but it’s not possible for you to move quickly in any organization without a sponsor.”

Banister believes his sponsors helped him continue to be given positions of responsibility, where he was tested “like you do with high potential people.” He kept passing those tests and moving forward within the system until 1998 when, as president of Shell Services U.S., he was reporting to the CEO of Shell Oil Company. As Shell Services globalized, he began working for the CEO of Shell Services International and spending a lot more time at Shell’s global corporate center in The Hague. Banister says, “That’s when things really started to spread out for me.”

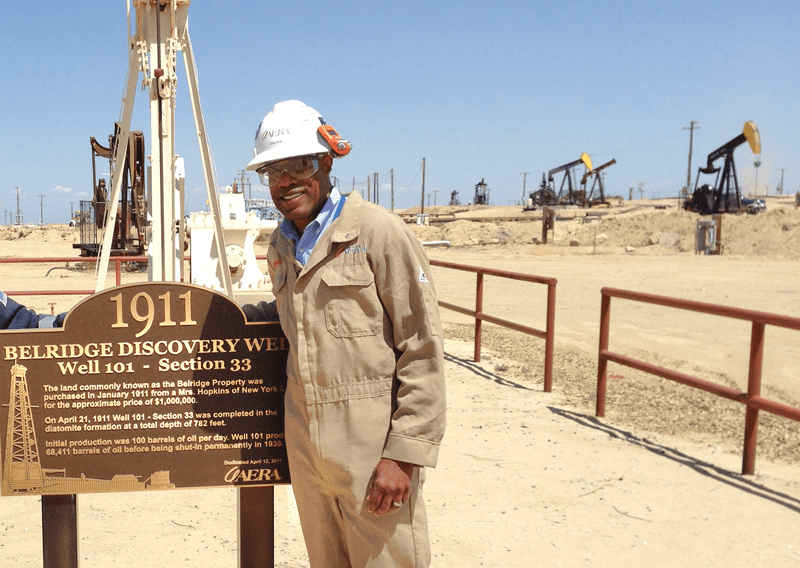

This meant traveling all over the world and ultimately accepting an overseas assignment. He was fortunate to spend several years in Singapore as vice president of drilling and development Asia Pacific (another lateral move), during what he calls “an amazing time.” Conversations started to arise about what to do next within the system and he told his supervisors he would like to run a venture, which eventually led to his appointment as the second CEO of California-based Aera Energy, a joint venture between Shell and ExxonMobil affiliates, where he succeeded founding CEO E.J. “Gene” Voiland in December 2007.

“None of these things happen in a vacuum. There’s this combination of performance, relationships and people who are willing to…” he pauses thoughtfully. After a moment he says, “There are white people – I’m going to use the word ‘risk’ – who are willing to take the risk and place an African American in a role that the company has not had one in and have confidence that they are going to be able to perform.”

“Context here is important. All bosses want team members that deliver and if you are one or perhaps two of the successful Blacks in the company then your white supervisors might feel they are taking a risk by moving you into unproven territory. You see, from my promotion to mid-level manager in the late ‘80s to the time I retired, I was one of the senior African Americans in Shell. I was generally the ‘first’ and the ‘only’ and I had to carry the aspirations of the Shell Black community with me in every role. I had people along the way who had confidence in me, starting with my first supervisor at Shell, Bob McConnell, to Frank Amato, the mid-level manager who encouraged me to take that first transfer to California to Greg Hill, who is now the president and COO of Hess.”

Peers at one point, Hill had been Banister’s supervisor in Singapore. “I know Greg had a role in me getting the job at Aera because he had the confidence that I could go and lead the company when Gene retired.” He gives credit to several other men, who gave him opportunities. “Phil Carroll had confidence in me taking over shared services when he was the CEO of Shell Oil Company [and] when Jack Little was executive vice president of Shell E&P, he had confidence in making me the general manager of the onshore business. I was really proud when I moved from Jack’s onshore business to serve as Phil’s president of Shell Services and when I asked, ‘Why me?,’ Phil said it was because they wanted my voice and experience at the Shell senior executive table. After becoming a senior executive, I gained support and friendship outside of Shell from colleagues in the Executive Leadership Council. ELC is a group of senior African Americans who are in, or report to, the C-suite in corporate America. I also had a ‘kitchen cabinet’ of advisors who would provide feedback and coaching to me on critical issues.”

Calling Aera a “world class organization,” with a strong reputation within Shell and ExxonMobil, Banister said it was his mission to build upon the foundation Voiland had established, something he spent eight years doing before deciding it was time to step down in 2015, when he passed the torch to Christina Sistrunk, the company’s first female CEO, with whom he remains friends. [Sistrunk, who was interviewed for the cover story of the September 2020 preview of Oilwoman Magazine, served as Aera’s CEO from 2015 until 2020.]

When asked about his legacy at Aera, Banister defers and says it’s best to ask the people who were there at the time. “I tried to lead in a people-centric way and to [create] a people-centric inclusive culture. People are not the most important asset in the business; people are the business – not assets that are bought and sold. It started with a focus on health and safety with the theme that ‘Every Day Everybody Goes Home Alive and Well.’ A phrase that everyone in and around Aera knows very well. At the end of the day, if people enjoy their work and say to themselves, ‘Thank God it’s Monday,’ not ‘Thank God it’s Friday,’ then the company has a shot at being world class. I was working toward making Aera a place where people felt valued and enriched by working there.”

Having already determined that eight years were the right length of time to serve as CEO, Banister made the decision to step down in 2015. “As difficult as it was, because I’m a loyalist and I cried at my send off, there was never one day that I looked back and said to myself, ‘I really wish I would have stayed longer at Aera.’ I wasn’t tired, frustrated, upset or angry; it was just time.”

Like many former CEOs, Banister has parlayed his knowledge and decades of experience to a seat on the board of directors of several Fortune 500 companies, including Marathon Oil, Tyson Foods and Dow, Inc., as well as other board seats. Pointing out that the directors don’t run the company (although they choose the CEO who does), he says, “Your job is to bring your expertise and talent to bear on the firm’s strategy, risk and CEO succession. Directors do this by asking questions and challenging the management team to be sure that they are operating in the best interests of the shareholders.”

Banister is well aware of the unique position he’s in as a Black Director. Despite the emphasis in recent years on diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), the Board Diversity Census, conducted by the Alliance for Board Diversity and the consulting firm Deloitte, noted that the number of Black men on Fortune 500 boards fell by 1.5 percent between 2018 and June 2020. (Black women’s representation rose by 18 percent, although they still hold a very small number of board seats.)

“Every day someone or something reminds me I am a Black man in America; that never ends,” Banister says. “The challenge is how we (as a society) move to a place where people are viewed equitably, where they get a chance, and we break down those systemic barriers that exist. That’s something that I continue to work toward.”

He adds, “I have an attitude of gratitude. I really have been blessed. I have had some phenomenal people who I had a chance to work with, who gave me a chance, who helped me be successful. I would add that given there are very few African Americans who have achieved my level of success in energy…that road was very difficult, and I worked extremely hard. I had to prove myself every step of the way and win over the skeptics.”

During our video interview, Banister has come across as somber and thoughtful, weighing his words and measuring each response, but he visibly brightens and then laughs when we talk about Different Points of View, the company he started with his wife, Simin, and two adult children, daughter, Nicole, and son, Julian. The name came about because, as he says, “We all think a little bit differently.”

From a family legacy standpoint, Banister and Simin decided that it would be best to set up a company, although, at least for now, he is the one most involved. While they each try to help people in their own networks, for Banister it has meant advising and consulting with companies and individuals on leadership and safety culture.

It is an incredible success story, one that is worthy of all the accolades Banister has received, but he started his career in the oil and gas industry over four decades ago. Even if his blueprint for success, which obviously worked quite well for him, were followed to the letter, is it realistic for prospective minority and female engineers to think that level of success can be attained in the energy industry today? After all, it was just in January of this year that a New York Times article painted a pretty grim scenario for the prospects of petroleum engineering majors and their future – if, indeed, they have one – in the industry.

Having lived through and survived 40 years of the cyclical nature of the oil and gas industry, Banister takes a philosophical view. “We are accustomed to boom and bust cycles. What we’re not accustomed to is the kind of challenge that’s happening because of climate change. From a reputational standpoint, the industry must respond much better than we have. We have got to make sure we have a serious strategic and integrated approach to participating in the energy transition.”

As Banister points out, historically the booms and busts have been tied to commodity price fluctuations and technology, whether it was 3D seismic, deepwater, horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing or other innovations, that helped revolutionize the industry. He theorizes that it’s possible the energy transition will usher in a new era of innovation and job creation for the industry.

“Fossil fuels are going to be around for the foreseeable future, so it’s important for the industry to put its resources toward enabling the transition.” Banister believes the increased investor focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) will lead to more transparency and therefore provide encouragement to young people to join the industry and help drive and create the innovation and technology that facilitate this new future. “It’s up to companies – and people – to deliver solutions for the world’s climate issues.”

“When I was at Aera, the phrase I used was, I wanted us to be ‘green minded.’” During his time as CEO, Aera became one of the first corporate offices in Bakersfield to have zero waste, with nothing going to the landfill, emphasizing his desire for the company and its employees to be aware of their environmental footprint. “We also had a massive recycling facility at Belridge that we used for all of our oilfield equipment and waste.” Citing recent court rulings, as well as activist investors, Banister challenges all companies to rise to the occasion and address one of the most pressing issues of our time. Otherwise, he says, the oil and gas industry runs the risk of becoming obsolete. “There’s too much at stake in terms of safe, reliable, affordable energy for the world for us to take that route.”

Although he’s retired, Banister’s board positions, the work he does with non-profits and his own company afford him a platform to continue promoting his people-centric philosophy, which benefits corporations as well as individuals. As he said during a July 2020 video interview with Katie Mehnert, founder of ALLY Energy, “Everybody counts when it comes to the people-centric culture that you should have in your business. The time when inclusion is most important is in a time of crisis. Every idea counts. Every idea matters.”

- A new skill or talent I learned during COVID-19 was…video conferencing on four different platforms – all of them are different!

- A goal I set for myself during COVID-19 was…to get better at golf. I am marginally better now (overall I was not great to begin with) and I do walk with a pushcart most of the time to help with my fitness routine.

- Currently, the books I’m reading are…Slavery By Another Name by Douglas A. Blackmon and The Second Founding by Eric Foner.

- I never miss watching…Get Up and First Take on ESPN weekday mornings.

- The first place I plan to go when it’s safe to travel or restrictions are eased is…Cabo San Lucas for R&R and Singapore for business. We have had a business/pleasure event in Singapore postponed for two years now and we all are anxious to go back.

- When I told my wife that I was going to retire, her response was…First, it was a joint decision like all family decisions. That said, her comment was, “You are too young; you need to find something to do.”

- The best thing about retirement is…I am busy but have no pressure.

- What I miss most about working full-time is…the opportunity to lead and engage with large groups of people.

- Something about me that would surprise people is…I was married 10 years before my wife convinced me to start eating tossed green salads.

- The person [living or historical figure] I would most like to meet and have a conversation with is…I’ve met presidents, politicians and business leaders. So, while engaging with a famous person is interesting, I would like to convene a family reunion of the elders on both sides – grandparents, great-grandparents, great aunts and uncles and others – to explore our family origins and history.

Headline photo courtesy of matsmithphotography.com.

Rebecca Ponton has been a journalist for 25+ years and is also a petroleum landman. Her book, Breaking the GAS Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (Modern History Press), was released in May 2019. For more info, go to www.breakingthegasceiling.com.

Oil and gas operations are commonly found in remote locations far from company headquarters. Now, it's possible to monitor pump operations, collate and analyze seismic data, and track employees around the world from almost anywhere. Whether employees are in the office or in the field, the internet and related applications enable a greater multidirectional flow of information – and control – than ever before.

1 comment

Comments are closed.